Green planes of the future … or just nice plans?

In an unfamiliar location, Airbus spent months testing a radical-looking aircraft. At ten feet wide, it’s only small, but it could be the start of something very big in the aerospace industry.

image captionThe Airbus Maveric is a remote-controlled blended-wing test aircraft

It looks like a flying wedge – known in the trade as a blended wing design.

Airbus calls the remote-controlled airplane Maveric and would like to emphasize that at the moment we are only investigating how the configuration works. But the design is said to have “great potential”.

One day it could be scaled to the size of a regular passenger aircraft.

In traditional aircraft, the fuselage is basically dead weight and needs large wings to keep it in the sky.

Google’s Wing warns new drone laws ‘may also have accidental consequences’ for privacy

Under one Mix-wing design, the entire airframe provides lift so it can be lighter and smaller than current designs but can potentially carry the same payload.

Maveric is one of several initiatives by Airbus, and there are many by other aerospace companies, to meet an industry target of halving emissions from aviation by 2050 compared to 2005.

“There really is one great challenge. And there is a great expectation of society, to which we believe we need to find answers, “says Sandra Bour-Schaeffer, Managing Director of Airbus UpNext, which evaluates new technologies for the European aerospace giant.

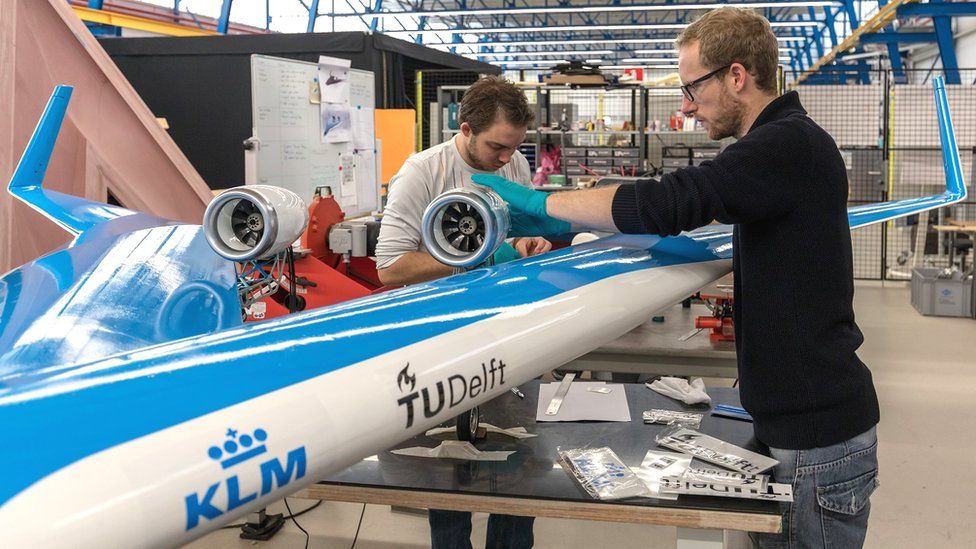

image caption A flying scale model of the Flying-V being prepared for tests

” We believe we have to go An equally radical idea is currently being explored at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands.

Researchers are working on a design known as the “Flying-V.” It’s a new concept for a long-range aircraft, one of which they claim they are up to 20% more efficient than a state-of-the-art modern aircraft like the Airbus A350.

. Like Maveric ver it dispenses with the idea of a conventional fuselage. The shape is more like an arrowhead, with two wings extending in a V behind the cockpit. Passengers and cargo would be carried within the wings themselves. The designers believe it would be cheaper to build than the combined wing because the two arms of the V could be “plugged” into the rest of the fuselage. Therefore, the aircraft could be built in parts, rather than all at once. We believe that we can keep manufacturing costs relatively low, compared to concepts that would have more unique components, “says Roelof Vos, the project leader for Flying-V and assistant professor at the Delft University of Technology.

The design was originally a graduate student creation and was part of his thesis, which is being developed with the support of the Dutch airline KLM and Airbus, and in July a scale model took to the skies for the first time, from an airbase in Germany.

The researchers said the machine performed well, although it suffered a kind of aerodynamic wobble, known as “Dutch roll.” It was difficult to keep the wings level and resulted in what they described as “a somewhat rough landing” that damaged the drivetrain. forward landing due to the pandemic, but despite that, KLM says it will continue to support the Flying-V investigation.

The attractions of more efficient aircraft are obvious, for an industry where cost control is vital to profitability and which is under heavy pressure to reduce its environmental footprint.

But the basic layout of commercial aircraft has remained unchanged for decades, there are other practical questions to consider – some of them are called “show stoppers” by avionics expert Steve Wright of the University of the West of England.

image captionThe Flying-V design would see passengers carried in the aircraft’s wings

Among them is how passengers get on and off the plane. In the case of the mixed wing, for example, the wide middle section could make the boarding process take longer, while passengers in the middle would be far from the exits in an emergency.

There is also the issue of passenger comfort. These sit close to the side of the aircraft – and effectively close to the edge of the “wing” – would experience much greater movement when the aircraft is in banking, while takeoff and landing would have to be steeper angles than normal.

The UK to start a new drone program following the example of Turkey’s Bayraktar

Building a new type of aircraft would also pose a challenge for the aerospace industry. Airbus, for example, manufactures sections and components of existing aircraft across Europe before they are taken to final assembly in Hamburg and Toulouse – a proven supply chain that leverages the expertise available in each region.

“This well-oiled manufacturing machine … it would certainly be strained and would have to be redesigned, “says Mr. Wright.

Airbus insists that issues like these are already being considered and would be considered as part of the design process, but there is little doubt that a design such as the Combined Wing or Flying-V would represent a significant gamble for a manufacturer. I spent years studying a concept that is less obviously radical but is still a clear departure from what we have now: the Transonic Truss-Braced Wing.

image caption Boeing’s Transonic Truss-Braced Wing design

An aircraft equipped with the wing would appear relatively conventional, with a central fuselage. but the wing itself would be much longer and thinner and would be reinforced by support, or truss angled upward from under the fuselage.

The wing would be folded to facilitate access to conventional airport gates. But the current research is not only focused on aerodynamics, there is also the question of how the aircraft of the future are propelled.

For short-range flights, with a limited n for a number of passengers, battery power could be viable. Projects like the Eviation Alice, which was shown at the 2019 Paris Air Show, are based on demonstrating that concept.

image captionAirbus is exploring the use of hydrogen for fuel in its Zero project

For longer distances, batteries are currently impractical, simply because they are too heavy and do not contain enough power to offset that weight. The industry has explored other options, such as hybridization, in which part of the thrust needed to fly is provided by

One of the main research projects was Airbus’ E-Fan X, a partnership between Airbus, Rolls-Royce, and Siemens, which involved the installation of a single 2MW (2,700 hp) electric motor, powered by an on-board generator, in a four-engine BAe 146-engined test aircraft. will build the world’s first zero-emission aircraft by 2035. Its plans are based on the creation of hybrid systems, using gas turbine engines that burn hydrogen and hydrogen fuel cells or generate electrical power.

In September, Airbus presented three Hydrogen-powered concept designs

Hydrogen fuel could even be combined with a radical design: one of the concepts included the combined wing. But here’s a major problem: Most of our hydrogen supplies today are derived from methane, a fossil fuel, which mixes with steam at high pressures, is an energy-intensive process, and creates significant amounts of carbon dioxide.

However, according to Glenn Llewellyn, Airbus vice president for zero-emission aircraft, society itself will eventually provide the fuel that is truly zero-emissions, the planes would need to be powered by hydrogen produced in a much more environmentally friendly way, and large quantities would be needed. . solution.

“Over the next decade, for society at large to comply with the Paris Agreement and meet our climate goals, we must switch to renewable hydrogen,” he explains.

BBC / TechConflict.Com