How JetBlue Founder David Neeleman Launched a New Airline During a Pandemic

Neeleman has overcome some crazy setbacks on his way to becoming the most successful serial airline entrepreneur in history

Photograph by Mackenzie Stroh

So why would he let a global pandemic get in the way of launching his latest carrier?

THE ICY WEATHER SYSTEM that trundled up the Atlantic Seaboard and glazed New York City on February 14, 2007, was nasty, but not the worst that airlines had ever confronted. Mainline carriers such as American and Delta knew the drill. They canceled flights in anticipation while moving equipment and crews to sidestep the storm and minimize disruptions. The newer kid on the tarmac, JetBlue, flew into the storm face first. And flopped.

The low-cost carrier was barely seven years old, growing rapidly and happily because customers loved its panache, pricing, and product–comfortable seating, free satellite TV, and freewheeling yet attentive flight crews. Concentrating its fleet in New York and Boston made the carrier more vulnerable to winter weather, though, and as the storm began to wreak havoc on operations, JetBlue swiftly learned that its communications and logistics networks had not scaled with the rest of the outfit. With crews stuck out of place, the airline would cancel more than 1,000 flights over five abysmal days, stranding customers from the Caribbean to Queens. One jet full of passengers sat on the tarmac for eight hours. The debacle ultimately cost the airline $30 million.

Hong Kong bars incoming Singapore Airlines flights over Covid-19 case

Even before the storm had passed, JetBlue founder and CEO David Neeleman were conducting a nonstop apology tour, vowing to upgrade systems and make things right by customers. “This is going to be a different company because of this,” he told The New York Times. He was right about that. Three months later, JetBlue announced that Neeleman was leaving the CEO post and becoming chairman. At least Neeleman wasn’t aboard a flight when his own board shoved him out the door.

If you are looking for a case study of an entrepreneur who gets repeatedly sucker-punched by exogenous events, Neeleman is it. He’s also a study in rebounding. In the early 1990s, he built his first airline, Morris Air, out of the wreckage of his own failed travel agency. He launched JetBlue less than two years before 9/11 grounded the airlines for weeks, curbed travel for a year, and bankrupted most of the industry. Then came that storm. “You can’t control everything,” he says now, without any particular malice. “I wrote an email to the crew and said, ‘It doesn’t really matter what happens to you in life; it’s how you deal with it.’ “

Neeleman began to build Breeze, his fifth airline startup, just before Covid-19 emptied the nation’s airports. That was after he’d returned from Brazil, where he started the wildly successful Azul Airlines in 2008. “I had 50 people hired for Breeze and we were moving along the track,” he says, munching airline snacks on a recent Monday in the upstart’s empty offices in the basement of a beige building in Darien, Connecticut. “It would have been easy for me to say, ‘Sorry, I just can’t do this.’ ” While major airlines, including Delta, United, and American, would get more than $50 billion in loans and grants from the federal government to weather the pandemic, Neeleman would have to plow his own money, some $30 million, into his fledgling business. (The company later got less than $1 million in PPP money.) “But a lot of the Breeze team left their jobs to come here,” he says, “and I just felt that I owed it to them to do it. So I said, OK, let’s make this happen. Let’s keep a foot on the brake and a foot on the gas.”

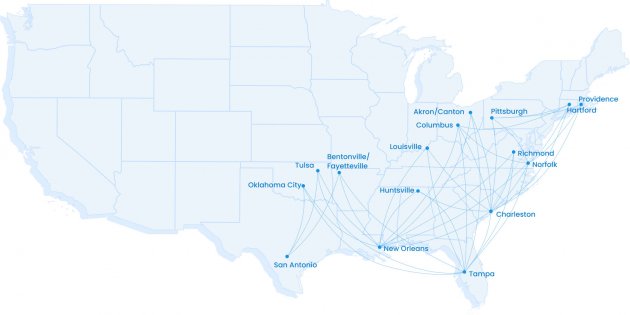

After more than a year-long takeoff roll, Breeze gets airborne on May 23 with flights in 16 cities beginning with Charleston, S.C., Tampa, Florida, and Hartford, Connecticut. The network will then expand through July 22 as far west as Tulsa, Oklahoma, and also including Northwest Arkansas (aka Bentonville, where Walmart is headquartered.) In October, Breeze will expand again when the first of its Airbus A220s arrive. Ticket prices will initially range from $39 to $89 one way.

We tend to think of the airline industry as a business with a high barrier to entry–all those pricey planes and terminals. But entry is not nearly so difficult as keeping an airline flying profitably over a long period of time, as dozens of defunct carriers (Braniff, anyone?) can demonstrate. Neeleman’s ability to spot opportunities and pair the right customer service with exacting operational efficiency has helped him defy the odds more often than any other airline entrepreneur. So has a sort of tunnel vision that comes with attention deficit disorder–a disability that led to one huge career setback but also fueled his success.

“There are two phrases I’ve heard a lot,” he says. “One is, ‘Well, David, if that was such a good idea people would have done it already.’ Really? The other is: ‘David, It’s not that simple.’ ” He pauses. “Well, yes, it is–it is that simple.”

U.S., EU to droop price lists in an attempt to remedy Boeing-Airbus subsidy dispute

THE HISTORY OF AVIATION is filled with dashing figures. Pan Am co-founder Juan Trippe was a true titan who made air travel glamorous in the 1930s and introduced the jet age. Eddie Rickenbacker, the unkillable racecar driver and World War I fighter ace, bought and built Eastern Air Lines. Howard Hughes, the wildly eccentric entrepreneur, airplane designer, and Hollywood producer, largely created TWA. Fast-forward and there’s Richard Branson, the music mogul who brought his personal Cool Britannia brand to Virgin Atlantic. And let’s not forget Herb Kelleher, a fun-seeking Texan lawyer who loved people, cigarettes, and Wild Turkey (not always in that order) and co-founded Southwest.

Then there’s Neeleman, just a guy from Salt Lake City. And it is he–a casual, approachable fellow in a fleece vest with all the menace of a suburban dad–who may prove to be the most relentless innovator of all. Breeze, whose inaugural flight will take off in mid-May, is a reimagining of what high-quality, low-cost air service can look like. Ever since JetBlue, Neeleman has, like the kid peering into the circus tent, longed to get back into the U.S. airline industry. But just wanting something doesn’t make a business plan, so for years, he looked for the right angle and moment.

The opportunity that revealed itself was this: The major players had not only plumped their profits in the past decade but had also plumped their costs. Their labor contracts had grown fatter–which was only fair, given their growing profitability. To compensate for rising costs, the big carriers were diverting more travelers through their hubs, where they could fill the bigger planes that they were buying.

Neeleman had seen this before–it’s a repeating cycle in his industry–and he knew it opened the door to flying directly between smaller markets. Allegiant, Spirit, and Frontier, which created the ultra-low-cost-carrier (ULCC) segment, had already taken advantage of that opening. Neeleman’s angle: Use technology to offer better service and a little more class than the ULCCs but keep fares just as low–and sum it all up for people by calling Breeze “Seriously Nice.” (The company originally toyed with the term “the world’s nicest airline.”)

So it is that Breeze takes wing in what is either the best or the worst time in history to start an airline. Worst because the big carriers have burned cash at a rate of $25 million to $30 million a day in 2021. Best because vaccinations and herd immunity will allow people to travel again freely. The breeze will be waiting for them with a fleet of 13 Embraer 190s and E195s. The company will add long-range Airbus 220s in the fall.

In the air, Breeze won’t pile people on top of one another, won’t slam them with excessive fees, and will offer three seating categories: Nice, Nicer, and Nicest–the last a value-priced business-class option on the A220s. At launch, Breeze will fly 49 direct routes from 15 cities, beginning with Tampa to Charleston, North Carolina; other cities include Pittsburgh, Nashville, and New Orleans. Think Rust Belt to Sun Belt.

The linchpin is a passenger app that Breeze will use to lower costs while removing friction and enhancing the customer’s experience–from reservations to check-in to baggage to ordering food or a ride home. “When I started JetBlue, it was a customer service company that just happened to fly airplanes,” Neeleman says. “Breeze is a technology company that just happens to fly airplanes.”

NEELEMAN, 61, got into the passenger aviation business through a side hustle that went upside down. He was born in Brazil, where his father was first a Mormon missionary and then a journalist. After growing up mostly in Utah, Neeleman, too, got sent to Brazil for his mission. After he came home, a University of Utah classmate related how a friend had time-shares in Hawaiian condos that he couldn’t move. Neeleman, who got started in business at the age of 9 in his grandfather’s grocery, asked for a meeting. In the deal he struck to market the time-shares, he’d pay the owner a set price per night, and anything above that was he to keep. He cleared $350 on his first booking; soon other time-share owners were asking for help too.

He took the next logical step, buying airline tickets in bulk at a discount and packaging them for his Hawaii-bound condo customers. Before long, he had a $6 million company. He dropped out of school. And then, shortly before Christmas 1983, he got a call from the startup airline that had been flying all of his customers. It was going out of business. Neeleman’s company, in turn, went bust returning money to customers whose vacations had been ruined.

Like his hero, Southwest co-founder Herb Kelleher, Neeleman is a people collector. And for Breeze, he got part of the JetBlue band back together.

June and Mitch Morris, who owned a Salt Lake travel agency, had taken note of what the young entrepreneur was doing. Under their wing, he set up shop again, this time as Morris Air–first as a charter service, and then as a scheduled airline. In expanding Morris Air, Neeleman and the Morrises studied Southwest and its CEO, Kelleher, intently, and they copied as much as they could in both operations and culture. By the 1990s, they had expanded to more than a dozen cities.

In 1993, June Morris, ill with cancer, contacted Kelleher to ask about combining their two companies. Southwest bought Morris Air for $129 million in stock, and Neeleman moved to Southwest as part of the deal. (Happily, June Morris would recover.) To Neeleman, it was a dream scenario, because he would get to work with Kelleher, his hero, and had a shot at taking over the company one day. “He led me to believe that if I minded my P’s and Q’s, I would be his successor someday,” Neeleman told NPR in 2019.

Five months later, Kelleher fired Neeleman. The reasoning: Even your biggest fans can’t take any more of you, Kelleher told him. Neeleman wasn’t minding his P’s and Q’s as much as obsessing over them, trying to make his mark on Southwest, and failing to keep his ADD in check. He’d been in charge of merging the two organizations over a two-year timeline. He’d gotten it done in six months but had driven his colleagues to distraction with his intensity.

Back in Salt Lake once again, Neeleman dreamed of starting another domestic airline, but he had signed a five-year noncompete clause. He looked to Canada and became an investor and co-founder of WestJet. And he thought about innovations he could bring to the industry even without planes. A relational database that Neeleman and a Morris Air colleague had developed to analyze fares, schedules, and profitability, as well as issue e-tickets, became the basis for a new reservation and data platform, Navitaire. It’s used by many airlines today, including Breeze. The pair sold Navitaire to Hewlett-Packard in 1998.

When he founded JetBlue in 2000, Neeleman leaned heavily on one of the concepts he’d borrowed from Kelleher: servant leadership. (The phrase was actually coined by AT&T exec Robert K. Greenleaf.) It’s a popular philosophy and simple concept: You work for your employees, not the other way around–and one of the key aspects is walking the talk. If you make it everyone’s responsibility to serve the customer, then you’d better do likewise, boss. Kelleher would regularly work onboard, serving drinks (naturally) and even helping clean planes–quick turnarounds were vital to Southwest’s success.

Neeleman transported the concept of happy people running a happy airline to New York. He moved his family east–not easy with nine kids in tow–and raised $135 million. And, like Kelleher, he set the tone by prowling JetBlue’s planes, serving beverages, asking customers how he could do better. And he helped clean the jets. “The more people you serve, the more lives you change, the happier you are too,” he has said.

Like Kelleher, Neeleman is a people collector. For Breeze, he got part of the JetBlue band back together. Critically, he added recruits from ULCC pioneer Allegiant, who brought with them strategic financial insights. “A lot of the team members joined for a similar reason: They worked with him in the past or they knew he was a visionary who could create something special,” says CFO Trent Porter, a former Allegiant executive.

“It’s his energy. His leadership style is so different from that of most CEOs,” says Doreen DePastino, Breeze’s vice president of inflight, station operations, and guest services and one of the JetBlue tribe. “He really wants to know his team members. People gravitate toward him.” When you combine vision with charisma, it’s easier to get people to buy into ideas that might seem far-fetched, such as putting a television screen in every seatback (a JetBlue innovation). “People would say, ‘This isn’t going to work,’ and all of a sudden we’d do it, and it would work,” DePastino says.

THE STRATEGIC CHALLENGE of running an airline boils down to this: Where do we fly, at what operating cost level, and how do we differentiate customer service? These are analogous to issues most businesses face, but in aviation, everything is magnified. At JetBlue and now Breeze, Neeleman has sought new answers.

The “where” question has been perhaps the easiest one to figure out for Breeze–because, even before the pandemic, both the major airlines and the ULCCs were giving up the turf. Partly because of their union contracts, which limited their ability to fly smaller jets, the majors were packing more people onto bigger planes. As the ULCCs matured, they did the same thing. “With bigger planes, you have to chase bigger and bigger markets,” explains Lukas Johnson, Breeze’s chief commercial officer, a job he held at Allegiant. Small and medium markets get left behind. “A lot of cities in the middle of the country haven’t seen a lot of seat growth in recent years,” he says.

The Breeze app is designed to eliminate chokepoints between passengers and planes. That means fewer people on the ground and lower cost.

When Breeze analyzed the data, it discovered a whole category of cities and routes being underserved. The FAA compiles a statistic called passengers daily each way (PDEW) that contains exactly where people are traveling and what they are paying on average. A market such as Huntsville, Alabama, to Orlando has relatively low PDEW because it’s inconvenient to fly between those two points; passengers have to change at Atlanta or Charlotte. In city pairs like this, Breeze thinks it can expand the PDEW exponentially by offering direct service. “Suddenly, people look at it and say I can fly there in an hour and for 59 bucks. I’m going to go three or four times a year. It just creates a market,” says Neeleman. (In this case, the market is called VFF, as in visiting friends and family.)

Breeze also aims to gain a cost edge in the types of planes it flies. Most airlines aim to optimize a metric called cost per available seat mile, which is measured against revenue per available seat mile–the general idea being that revenue should exceed the cost, which is variable. At Azul, Neeleman came to understand that an airplane’s trip costs–the fixed costs–could be just as important in gaining a competitive advantage. And that’s where an efficient Airbus 220-300 could win. Running that jet, for instance, costs just a third of what the larger A321 costs. The bigger jet may have a lower average seat cost, but has much higher total costs, especially as the distance expands. “In that case, the lower trip cost wins,” says Johnson.

There’s no formula for the third leg of Breeze’s strategy, which the company, after some refinement of the catchphrase “the world’s nicest airline” now calls “Seriously Nice”. One thing nice is not saying Neeleman is an employee who smiles at you after you’ve waited in line for 30 minutes. The Breeze app is designed to eliminate chokepoints between passengers and planes. That means fewer people on the ground and lower cost.

Breeze is also introducing a program in which it will hire college interns from Utah Valley University and mold them into customer service machines. In exchange for a salary, free tuition, and housing, the students will undergo training and then work 15 or so days a month while taking their college courses online. “The big thing is we are going to provide a great service with kind people on a beautiful airplane with a fun atmosphere,” says DePastino.

As Neeleman has prepared for Breeze’s launch over the past year, the pandemic has changed the industry’s chessboard in the company’s favor. The majors were forced to drastically reduce their fleets, retiring the least efficient jets and abandoning marginal markets wholesale. That’s a scenario made for Breeze. “Larger markets are on our list now,” says Porter. “The total space we can address is actually larger.”

That window won’t be open for long. The recovery of the domestic airline industry is gaining momentum by the month, and airlines are restoring service as fast as they can. Airports and jets will fill. There will be more and longer lines and customers with frustrations. Neeleman, who cannot abide lines–they signal inefficiency and inattention to customers–will be there observing, serving the occasional customer himself, and always, always looking for new angles. “It drives me crazy when I go to an airport and walk by Starbucks and there are 50 people in line,” says a man who doesn’t even drink coffee. “How in the hell can we reimagine this whole thing?”

The data suggests that roughly one new airline a decade actually thrives. Neeleman’s done it an unprecedented four times and thinks he can do it again. His record suggests it should be a breeze–albeit with occasional turbulence.