The Rise and Fall of a U.S. Oilman in Iraq

A secret kickback deal with an Iraqi Kurdistan politician made Todd Kozel rich. But an affair and his bitter divorce led him to disgrace

The Iraq war was good to American oil baron Todd Kozel. As the country was in the midst of a full-blown insurgency in 2007, his London-listed firm Gulf Keystone signed an agreement with the government of the autonomous region of Kurdistan to exploit its “oil field of dreams.”

The very same day in November, OCCRP has discovered, he struck a deal to kick back potentially huge revenues to a veteran Kurdistan politician’s company in order to secure the oil block.

The deals –– one public and official, the other secret and illegal –– transformed the fortunes of Gulf Keystone and its founder. The company’s operations are now entirely based on the block in question, named Shaikan.

Kozel made more than US$100 million and began to live a lavish lifestyle, flying by private jet and splashing out thousands on fine wines and strippers. He also began an affair that would sow the seeds of his downfall when his subsequent divorce pitted the playboy against his socialite ex-wife in court. The case dredged up previously unknown details of Kozel’s finances, which eventually led to charges against him.

Kozel pleaded not guilty in 2019 to fraud and money laundering. After a secret plea deal, prosecutors downgraded his charges to failure to file tax returns, saying he owed over $22 million on the fortune he made between 2011 and 2015. He pleaded guilty to the lesser charges. Now suffering from throat cancer, Kozel is scheduled to be sentenced at a hearing in New York this summer.

Todd Kozel with his wife Inga in a photo posted to her Instagram account

Kozel’s deal with a company controlled by Izzeddin Berwari, a member of the governing Kurdish Democratic Party’s (KDP) politburo, has not been reported until now. By 2010, Gulf Keystone and the government of Kurdistan had privately agreed that the deal was illegal, and treated it as void, but kept the broader oil concession in place.

A spokesman for Kozel told OCCRP the deal had “nothing to do” with Gulf Keystone receiving the oil production contract.

“These claims from more than a decade ago have been investigated, litigated, and adjudicated, with no findings of corruption, fraud, or a failure to disclose by Mr. Kozel,” the spokesperson said.

With the help of a whistleblower, sources familiar with Kozel’s years at the helm of Gulf Keystone, and hundreds of court records and corporate filings, reporters have pieced together the story of Kozel’s rise and fall.

As well as the kickback deal, Kozel is also connected to a company that received a controversial $12 million payment from Gulf Keystone in 2010, according to documents seen by reporters. The finding supports the suspicions of Kozel’s ex-wife that he personally benefited from the arrangement.

A spokesman for Kozel said that he was neither a shareholder nor executive of the company that received the $12 million, nor did he have any management control.

Court papers also show how he profited from insider trading, secretly buying and selling shares through an offshore trust in Jersey, a British Crown Dependency. One trade took place the same day oil was first struck at Shaikan — but three days before shareholders were informed.

A spokesperson for Kozel said the trades were investigated by British officials, who found no violations. (Stock exchange officials and financial regulators would not confirm or deny the existence of any investigation to reporters)

The fact that Kozel got away with the trades highlights the City of London’s blind spot for secretly-owned offshore companies. Despite a stream of scandals, often centered around these opaque corporate vehicles, London’s Alternative Investment Market, where Gulf Keystone was listed until 2014, has done little to address the issue.

War and Oil

When the U.S. and the U.K. invaded Iraq in 2003, Kozel was just another “wildcat” explorer looking for black gold beneath the sand. He had an operation in Algeria, but it was nothing compared to what he would go on to establish.

“I thought I had been a master of the universe,” he later said. “But I found out there was a much bigger universe than I was even aware of.”

The new universe began opening up in Kurdistan, an autonomous region in northern Iraq that welcomed international oil exploration. On November 6, 2007, Gulf Keystone landed the rights to the Shaikan oil field, which Kozel claimed could yield up to 15 billion barrels –– more than 20 times the eventual reserves figure. It was what he described as “virgin territory… an oil man’s dream.”

An image of the Shaikan oil field taken from a Gulf Keystone promotional video

After it announced its first find in August 2009, the oil company was transformed into a hotly traded multimillion-dollar enterprise. Its market value leaped from 359 million British pounds to 3 billion. Kozel’s yearly compensation peaked at $22 million in 2011, one of the highest CEO pay packages in the U.K., and nearly $7 million more than the head of Shell received that year.

But such generosity would not have been possible without a secret agreement Kozel signed on November 6, 2007, with Berwari, the Kurdish KDP politician, who also ran an influential company called Dabin Group, based in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Izzeddin Berwari pictured in a promotional article for the Dabin Group

Under the terms of this deal — which was called a “Representation Agreement” and contained an expansive confidentiality clause — Dabin Group, with Berwari as executive chairman, was to provide “general consulting and government relations services related to securing and subsequently managing” the oil concession.

Dabin would also be tasked with “arranging meetings with and introductions to political and financial organizations and individuals in Kurdistan and Iraq.”

In exchange, it was promised 10 percent of Gulf Keystone’s net revenues from operating the oil field, for up to 25 years.

The existence of the agreement between Kozel and Berwari has never before been reported. However, it was presented as evidence in a London court case that ran from 2011 to 2013, which was brought by a company run by former U.S. special forces soldier Rex Wempen, who had acted as a fixer for Gulf Keystone and claimed he was owed millions for helping it obtain the oil field.

The judgment in the court case revealed that on November 5, 2007, a day before the Representation Agreement was signed, Kozel enjoyed a barbeque at Berwari’s home. They were joined by Iraqi Kurdistan’s Minister of Natural Resources Ashti Hawrami, who along with the prime minister and his deputy, was in charge of granting oil concessions.

An oil consultant before the Iraq war, Hawrami owned a large home in the well-heeled British town of Henley-on-Thames. As the judge noted, the minister had a relationship with Kozel going back to before his appointment, and a subsidiary of Hawrami’s company had prepared a report for Gulf Keystone ahead of a share issue three years earlier.

While Gulf Keystone won the case against the ex-soldier, the judgment detailed a series of events in early 2010 that led the company and the Ministry of Natural Resources to agree that the profit-sharing agreement with Dabin violated Kurdish oil law. The law prohibits a public officer like Berwari from acquiring “a benefit or an interest” in an oil concession, directly or indirectly.

Ashti Hawrami at Chatham House in London in 2010

Hawrami knew the oil law well, as the official responsible for pushing it through Iraqi Kurdistan’s parliament in 2007. Despite the conclusion that the Representation Agreement was illegal, the Kurdistani government did not cancel Gulf Keystone’s oil production deal as required by law.

Instead, in August 2010, Gulf Keystone and the government signed an amended contract that included a new anti-bribery clause, which explicitly stated that no public or party official was being paid as part of the agreement.

But as Dabin Group was dropped, a new offshore company with no history or track record called Etamic Limited, which had signed an agreement with Keystone a year earlier, would grow in prominence.

In the judgment, Lord Justice Christopher Clarke said the Dabin Group also appeared to have had connections to Nechirvan Barzani, prime minister of Iraqi Kurdistan at the time.

Gulf Keystone wrote to the Dabin Group canceling the agreement only months before the U.K.’s Bribery Act, which brought tougher rules against international corruption, was passed in April 2010.

But the deal may have breached an earlier law, the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906, under which anyone who “agrees to give or offers” inducements for showing favor “to his principal’s affairs” is committing a crime. The Act was extended in 2001 to specifically cover bribery of foreign public officials.

The agreement may also have breached the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which makes it illegal to offer or authorize bribe payments to public officials, whether or not the money is ultimately paid.

While it was Berwari’s position in the KDP politburo that was at issue in this case, wider allegations have been made against the Dabin Group. A Kurdistani academic said in his 2017 Ph.D. thesis that the Dabin Group runs the ruling party’s businesses. He cited a KDP official saying it was the only KDP-controlled company in Iraqi Kurdistan, although others were controlled by individual party officials.

OCCRP contacted Izzedin Berwari and the Kurdish Democratic Party about the 2007 deal but did not receive any comment. Lawyers for Hawrami and the Kurdistan Regional Government said neither of them had any relationship with Dabin Group or received payments from the company.

“Moreover, neither the KRG nor Dr. Hawrami is aware of any illegality in arrangements between GKP [Gulf Keystone] and Dabin (to which they were not party),” the lawyers said.

The London judge did not address the corruption issue, which was not central to the claim made by Wempen, the former U.S. special forces soldier.

The corruption evidence was not discussed officially again until March 2014, when a whistleblower in Iraqi Kurdistan contacted the U.K.’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) about Gulf Keystone. OCCRP has seen a copy of the complaints filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, the Department of Justice, and the FBI, as well as correspondence that followed.

The whistleblower wrote that the Representation Agreement appeared to be a “written corruption agreement.” In follow-up correspondence, he said the deal may have “constituted a serious crime, in multiple legal jurisdictions.”

The deal, the whistleblower wrote, would have “violated US, UK, and Iraqi corruption laws, because when Gulf Keystone signed it, they had contracted with Mr. Berwari, who is himself a high-level official –– never mind his connection, or the Dabin Group’s connection, to the Prime Minister.”

The whistleblower also pointed to Article 56 of the Kurdish oil law, which specifically states that when a minister finds a breach of corruption laws, he “shall cancel” the offender’s contracts.

“The word ‘shall’ indicates that the Oil Minister is given no discretion,” the complaint said. “If he finds out about corruption, he must cancel.”

Authorities in the U.S. and U.K. stayed in contact with the whistleblower for another two years, but then lost touch and did not take any public action.

Ed Davey, of the anti-corruption group Global Witness, said the arrangement raised red flags and should be fully investigated.

“The existence of a written agreement promising to pay a senior political office as part of an oil field deal is highly concerning,” Davey said.

“It beggars belief that the Serious Fraud Office would not fully investigate a U.K.-listed company in such circumstances.”

The SFO told OCCRP it could not comment on the case.

Lawyers for the former oil minister, Dr. Hawrami, say there is “no basis to allege any wrongdoing or lack of integrity” on his part. “On the contrary, the integrity of the KRG [Kurdistan Regional Government] and Dr. Hawrami is a matter of record and beyond reproach.”

They added that the Kurdistan government “has a rigorous policy and practice of conducting negotiations” for oil contracts and does not work through agents or middlemen but “directly with parties that have an established track record.”

A spokesman for Gulf Keystone said: “The questions raised concern the period when Mr. Todd Kozel was CEO of Gulf Keystone Petroleum Ltd, with a particular focus on events between 2007 and 2010. This predates the appointment of any of the current board or management team.”

“The Company is committed to the highest standards of corporate governance including ensuring we undertake appropriate due diligence and third party professional advice and has an appropriate share dealing code, disclosure and compliance procedures, including for all officers and employees of the Company. In accordance with these standards, the Company considers with all due process any new matters that are supported by credible evidence.”

A spokesman for Kozel denied Dabin had played a role in Gulf Keystone securing the oil contract, and stressed that the deal had been voided.

Trusts and Lies

As Kozel was becoming a very rich man, he met Inga Buividaite, a Lithuanian student and model, then in her early twenties. They began an affair that ended his 18-year marriage to his wife at the time, Ashley.

In a January 2012 divorce settlement, Kozel agreed to hand his former wife 23 million shares in Gulf Keystone, worth well over $100 million. But she accused him of delivering three-quarters of the shares late and sued him in Florida.

The delay was notable because Gulf Keystone shares peaked on February 20 that year, but their value had begun to plummet by the time Ashley acquired most of them in late February and early March. She alleged that her ex-husband had stalled in order to stash money away via a trade involving a secretive Jersey trust.

Ashley Kozel won the case in September 2015 and was awarded $38.5 million. Todd Kozel said he couldn’t pay, so she began hunting for his money through the courts.

The lavish lifestyle of Todd Kozel and his new wife, Inga, was swiftly exposed. There were payments for two Hermès “Birkin bags” for 28,000 British pounds ($38,493), another 24,000 euros ($28,539) to French fashion house Chanel Haute Couture for a black wool dress, and $1.54 million on a diamond and a pair of earrings from Graff Diamonds in New York.

The Gulf Keystone chief executive was also claiming major work-related expenses. In his deposition, he admitted to spending nearly $8,000 at a strip club in Zurich, “where we entertain our customers and company members, which is reimbursable.”

“When we do it, we take a lot of people and we do it properly,” he said.

Ashley Kozel’s lawyers also began asking questions about another mysterious company, based in the British Virgin Islands, that had dealings with Gulf Keystone. They suspected her former husband secretly owned the firm, called Etamic Limited, and used it to siphon money from his investors.

The company seemed to appear out of the blue in July 2009, when Gulf Keystone suddenly announced it would be handing Etamic — which it described as its new “strategic investment partner” — half of the subsidiary holding its Iraqi Kurdistan assets.

Etamic was described only as a “private investment fund in the Middle East,” and there was no mention of its owners or directors. Gulf Keystone’s finance director, Ewen Ainsworth, said the fund’s owners had “asked us not to say too much about them,” according to Gulf States Newsletter.

There were also no records of the deal. Kozel later claimed that this was because it had been concluded verbally. “It was a strange deal,” he told a London court.

Minutes of a September 2009 board meeting said the government of Iraqi Kurdistan had approached Kozel with the proposal.

John Gerstenlauer, Gulf Keystone’s chief operating officer at the time, told a judge Etamic had been brought to his firm “by Dr. Ashti [Hawrami] and The Ministry of Natural Resources and the KRG.”

Kozel also told the court that Hawrami had “brought the investors and the idea” and that he had then asked his lawyer “to try to put together a structure.”

Dr. Hawrami’s lawyers strongly deny that he introduced Etamic to Gulf Keystone. “On the contrary, the policy and practice of the KRG prohibit the use of such intermediaries.”

In return for obtaining a major stake in the valuable Shaikan oil field, Etamic would help Gulf Keystone acquire rights to two unproven fields in Iraqi Kurdistan, called Sheikh Adi and Ber Bahr. It is not clear how Etamic would do that, or what influence it had in Kurdish oil circles.

Eight months later, Gulf Keystone said it was ending the relationship with Etamic “following a material default,” and would need to pay the mysterious company $12 million “for them to go away,” as the finance director put it. Gulf Keystone said it was left saddled with further costs, including $40 million owed to the Iraqi Kurdistan government in “infrastructure support payment.” Gulf got to keep the new oil licenses, but relinquished them in 2016, by when it had become clear they were essentially worthless.

Ashley’s lawyers suspected that Etamic was one of Kozel’s “alter egos,” used to funnel money away from the company and into his pockets. The Evening Standard reported in 2009 that there were “scurrilous questions over whether Etamic might in fact be linked to Gulf Keystone directors.” Gulf Keystone denied this.

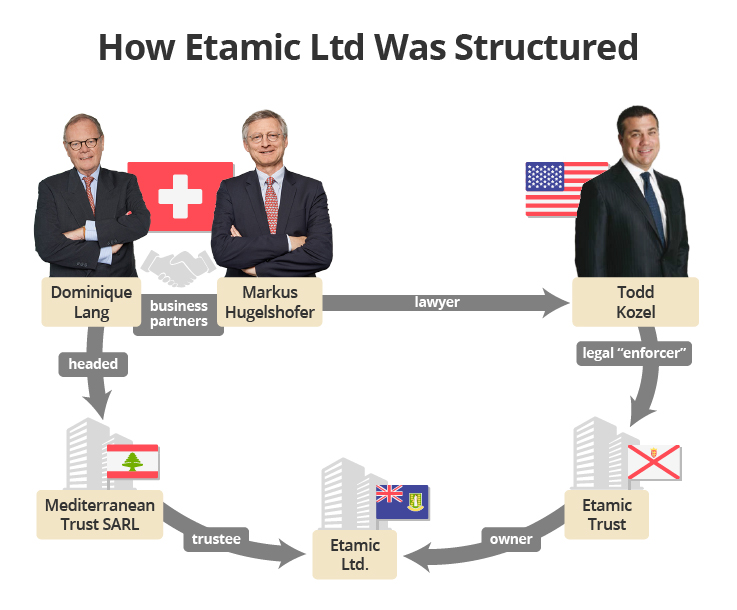

But a draft trust document seen by OCCRP shows that Kozel did have a direct personal connection to the offshore company. It states that he was to be the legal “enforcer” of the Etamic Trust, based in the tax haven of Jersey and owning Etamic Limited in the British Virgin Islands.

The trust was tasked with handling infrastructure payments and Kozel was specifically allowed to receive money from it. His ex-wife alleged that Etamic was actually a secret way for Kozel to hide his wealth.

There were further connections too.

Etamic’s trustee was a Lebanon-based entity called Mediterranean Trust SARL, headed by a Swiss banker named Dominique Lang. Lang was a close business partner of Kozel’s Swiss lawyer, Markus Hugelshofer.

Other evidence in court documents supports the idea that Kozel secretly controlled Etamic. Quizzed on the company during the divorce case, he was cagey, saying he believed his Swiss lawyer had helped form the Etamic Trust, and that the trustees were “two bankers in a bank in Beirut.”

It turned out that Kozel actually had close connections to these “two bankers.”

The bank in question, it eventually transpired through cross-examination, was the Near East Commercial Bank, which was owned almost entirely by Lang and two of Hugelshofer’s close legal partners. It was Lang who signed the $12 million “termination agreement” on behalf of Etamic.

One month before the July 2009 deal with Gulf Keystone was announced, Etamic’s name was changed in the British Virgin Islands corporate registry to Limonara Ltd. But in public statements, Gulf continued using the old name. The Swiss bankers and lawyers linked to Kozel had made it almost impossible for anyone to track Etamic down.

A spokesman for Kozel said Gulf Keystone was unaware of the name change, adding that all aspects of the Etamic deal were approved by the government of Kurdistan and Gulf Keystone’s board.

Cape Verde Court Approves Extradition of Maduro’s Ally to the US

The IRS Arrives

Ashley Kozel failed in her legal bid to get documents about Etamic, but she had more luck with another Jersey trust, named Gokana, that she and her lawyers suspected was controlled by her former husband.

Gokana was formed in 2009, and in August that year became a 6.4-percent shareholder in Gulf Keystone. It was later established that Kozel was issuing instructions to Gokana. But contrary to stock market rules on “related parties,” he did not declare his links to it. All directors, including Kozel, regularly informed the stock market of their direct or indirect holdings in Gulf Keystone, but Gokana was treated as an independent entity and never included in Kozel’s tally.

This allowed him to hide the shares not only from his ex-wife but also from stock market authorities and investors. Court transcripts and corporate filings show that Kozel secretly bought millions of Gulf Keystone shares through Gokana on August 3, 2009 –– the same day the company made its first oil find in Iraq, and three days before the find was publicly announced.

Kozel used his Swiss lawyer, Hugelshofer, to hide his hand, court documents show. First, he lent Hugelshofer –– as the Gokana trustee –– 968,000 British pounds, then Gokana bought the shares.

The announcement of the oil find on August 6, 2009, immediately sent Gulf Keystone shares rocketing, doubling in value in just a day.

By April 2011 the company’s stock had risen by over 1,000 percent, by which time Gokana had sold some 1 million of its shares, according to calculations by OCCRP. This sale alone, which exhibited all the signs of insider trading, could have earned Kozel over 1 million pounds in profit.

Kozel’s maneuvers with Gokana bore the hallmarks of “related party fraud” –– secret self-dealing through which company officials funnel investors’ money into their own pockets.

How Stock Exchange Scammers Get Away With It

“Related party fraud” has been at the heart of numerous scandals on London’s Alternative Investment Market (AIM), the junior stock exchange where Gulf Keystone was listed until March 2014. Yet the exchange continues to allow unscrupulous people to keep their offshore interests hidden — largely because no one is checking.

On both the main London Stock Exchange and the AIM, companies are asked to declare their shareholders, including the ultimate owners of companies or trusts that own stakes. But multiple auditors, lawyers, and privately nominated advisers (or “Nomads”) responsible for overseeing companies on AIM told OCCRP that these declarations are often taken at face value, and documentary evidence on the true ultimate owners isn’t always sought out.

The lack of scrutiny means that firms can pay millions into anonymous offshore companies or trusts that are secretly owned by directors of listed companies.

Nomads ask directors to declare any “related party” interests but rely on their word, said an executive at a leading Nomad firm. While Nomads sometimes hire due diligence companies to do further checks, there is no guarantee this would uncover the ultimate beneficiaries of a deal involving offshore companies.

Since Nomads are the “primary advisers” on AIM, directors can lie with little fear of being caught out — it is rare for the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority to step in.

Government regulators “don’t look behind the veil” on company ownership, said a corporate lawyer who specializes in listings on the main exchange. “You make disclosures to them, and they assume everything is accurate.”

Paul Gilbert, a University of Sussex lecturer who has studied AIM, says the exchange has not improved its oversight over the past few years, despite many related-party fraud scandals, including the one involving Gulf Keystone.

“There does not seem to be any significant evidence that AIM regulations have tightened in a manner to ensure that we no longer see the kinds of disciplinary failures which occurred,” he said.

Since 2015, AIM has shown a growing tendency to discount or waive fines on Nomads for their failures, he said.

A leading Nomad said AIM regulation has become more demanding towards Nomads, but that it needed to focus on “digging out the proper dirt.”

“We all agree that the bad guys need to be weeded out,” he said.

Kozel’s divorce, meanwhile, had also caught the attention of the Internal Revenue Service.

A September 2015 Florida court judgment awarding Ashley Kozel $38.5 million said Todd Kozel had falsely claimed in court that he had no authority over Gokana. The same court said that Kozel dealt in shares through the trust, and tied it to Kozel’s purchase of a luxury Manhattan apartment.

The 2015 judgment was later overturned on the basis of the couple’s divorce agreement, but that decision did not call into question the fact that Kozel secretly controlled Gokana.

Kozel was arrested at New York’s JFK airport just before Christmas in 2018 and charged with fraud and money laundering. The New York indictment said he had “lied in sworn affidavits and documents filed in the Florida Court when he said he had no interest in the Foreign Trust,” referring to Gokana, which was used in “a scheme to defraud his Ex-Wife.”

The prosecution maintained its fraud and money-laundering charges for eight months, but then signed a plea agreement, which was placed under court seal until journalists working with OCCRP successfully applied for it to be unsealed.

The document shows the court will accept a guilty plea on five counts of failure to file tax returns and Kozel will face a sentence of 60 months in prison at most and no further charges. He will have to pay around $22 million in back taxes.

“Looking back now,” the whistleblower in the case told OCCRP, “it seems almost certain that his luck would eventually run out, and that he would ultimately suffer a very hard fall.”

“In reality, however, there are countless businessmen out there just like Todd Kozel, and they do in fact get away with it.”